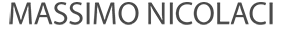

Patron saint of the city of Catania, Agatha of Sicily was martyred in 251 AD, at the behest of the Roman proconsul Quintian, who fell in love with her. Every attempt at seducing the girl was to no avail, because Agatha devoted herself to God at 15 years old.

After numerous rejections, the proconsul had her tortured. First, her breasts were torn off with large pincers, but a vision of St. Peter saved the young maiden. A powerful earthquake began and Mount Etna started erupting when Quintian ordered for her to be burned at the stake. Yet, again, Agatha survived, thanks to a red veil she was cloaked in.

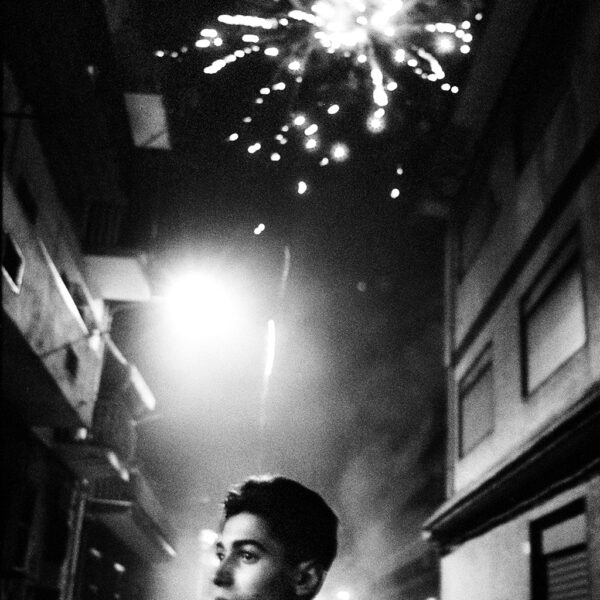

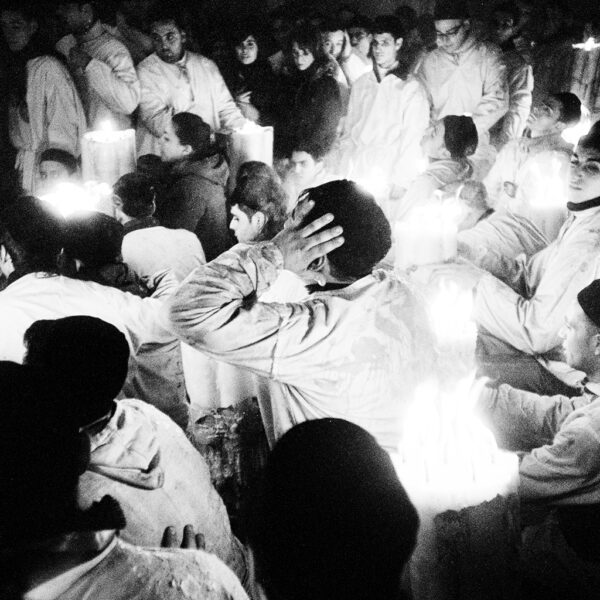

Removed from the stake and brought to prison, she died on the night of February 5, 251. Her body was embalmed, swathed in the same red veil, and carried back to Catania’s Cathedral Square. The population took to the streets in their nightgowns to welcome the saint and escort her to church. As Agatha’s body entered the holy grounds, Mount Etna stopped erupting and the earth stopped tremoring.

I remember the Festival of St. Agatha from my childhood as an event full of mystery. Together with my family, I have seen and beheld it numerous times, and I especially loved the stories and legends that were told around the saint and the circumstances of her death.

Photography was a sheer pretext to return to this familiar past. An opportunity to dig into my heritage, a history tied up with holiness and folklore – like the Festival of St. Agatha – and bond with the land that treasures it.

For several years, I covered the event as a photographer as well as to pursue those feelings that I wanted to experience closely and firsthand. I was trying to find myself in the place I had left very early to build a life somewhere else.

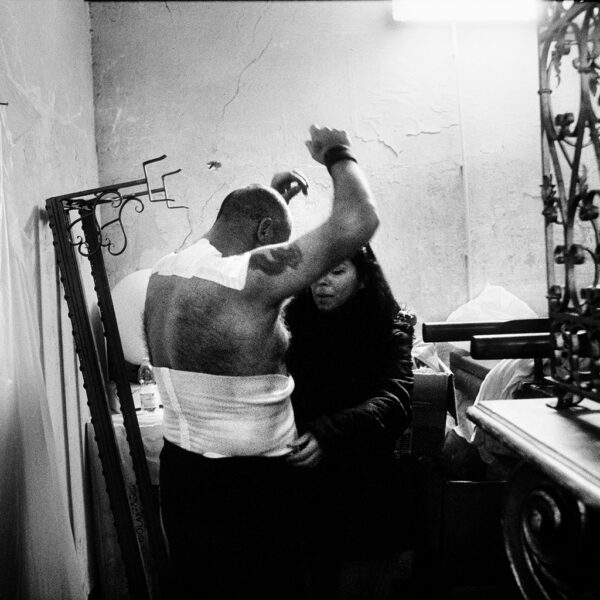

The Festival holds the record as the most attended religious festival in Italy and third in the world – after the Holy Week in Seville and Corpus Christi in Cuzco – it is characterized by a range of elements and the whole city takes center stage during the three days of celebration.

Among the typical elements of the festival are the cannelori: standing between 13 and 16 feet tall these huge votive candles consist of a wooden structure decorated with angels, gold-colored sacred figures, flowers, flags, and lights. The cannelori represent the crafts and trades of the city of Catania, they are carried by as many as 8 to 10 people, and pay homage to the patron saint. The most ancient and historical among the eleven Cannelori are the Cannelori of the Greengrocers, of the Butchers and of the Fishmongers, followed by the Cannelori of the Bakers, of the Pizzicagnoli, of the Florists and others. The parade kicks off the festivities on February 3rd, the day before Saint Agatha’s Day. On February 4th, they precede the exit of the reliquary from the church. At the crack of dawn on the 6th they await the return of the relics to the Cathedral’s Square, where they lead the way for the outspread cordon of devotees, who throw themselves into the streets to pray and greet the patron saint.

It is safe to say that the cannelori hold a parallel, stand-alone celebration and procession.

These immense candles are miniature monuments to the history, age and tradition they represent. When carried around the streets of Catania, they give the impression of a dance – pare che nacano – because of the unique movement imparted by the bearers.

No one owns these monuments, but a handful of chosen families have had them in their custody and care from time immemorial.

The bearers of each individual cannelora are selected and directed by people who work throughout the year on the festival’s preparation. We could compare cannelori to football: each club has its own board, staff, players, ambitions and, as in sports, there is the cannelora that has the longest tradition and greater prestige, but this also entails more effort, while a more recent one may be less demanding.

What may look like mere folklore to a layman, has precise and unbreakable rules at its core. For example, the careful selection of carriers ensures a homogeneous team, with the young and powerful at the back, pushing the entire group, and the more experienced men at the front, regulating the pace, the timing and the stops. The formation of the cannelori teams changes every year, the recruitment of the boys who will join a cannelora is carried out during the entire year, through connections, negotiations, displays of interest, proposals, glances, winks, all of which begins during the previous festival for the following edition.

Since childhood, I have heard legends about the cannelori and their bearers. It is said that mafia money revolves around it, that the bearers use special drugs to sustain such an immense effort, that mafiosos at large come out of their hiding places to partake the bear of cannelori, and that there are frantic rounds of underground gambling around them.

I first photographed the procession in 2008, from then on, I did not stop until 2019.

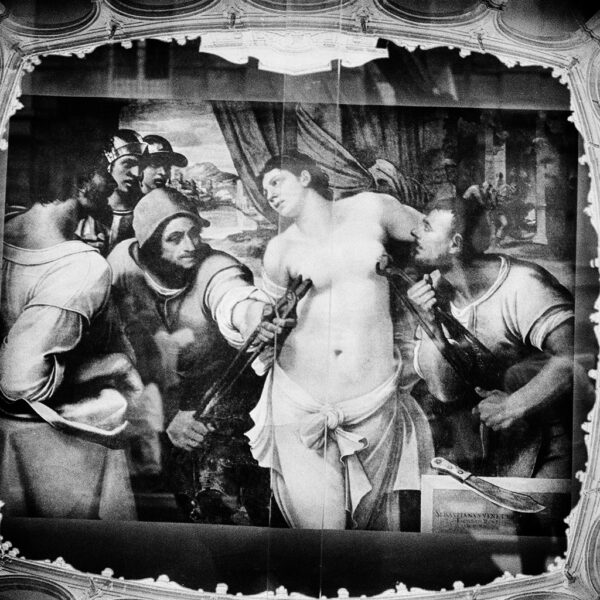

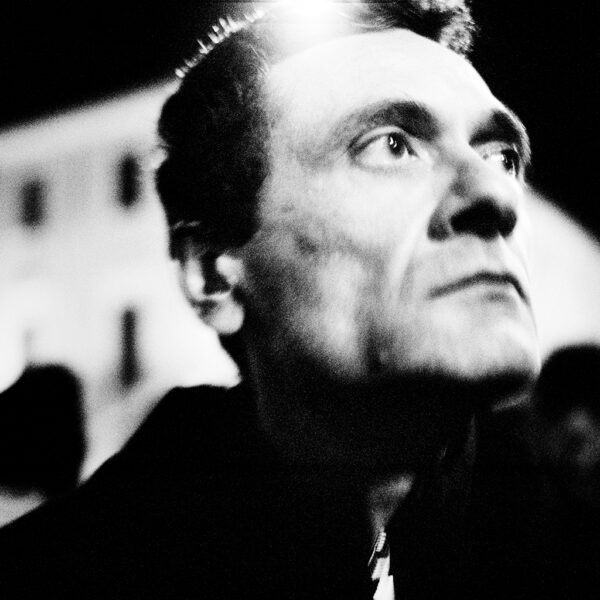

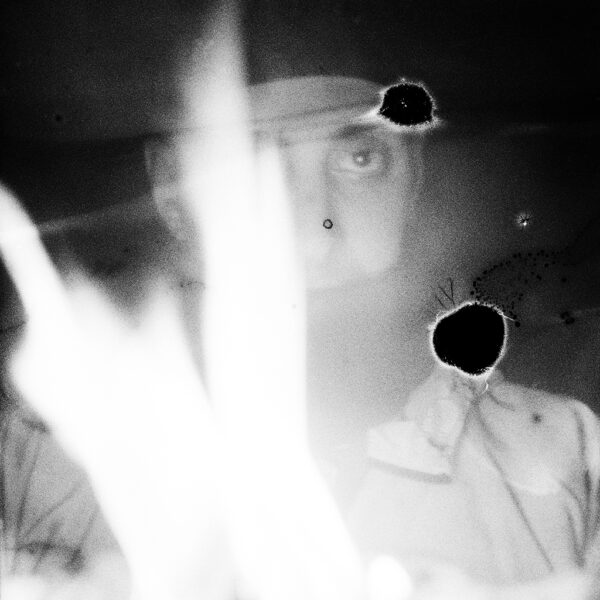

After the first few years I realized that the Festival of St. Agatha itself played only a part (and a small one) in my fascination. The moment that caught my attention the most was undoubtedly the most pagan and human aspect of the event, the night of February 5th, when the devotees carry these monumental flaming candles on their shoulders for hours.

My interest has only grown over the years, enriched by stories, legends, and anecdotes that tie to my childhood and brought me face to face with a culture, an unfamiliar humanity, that lived at a different speed than I did, therefore posing questions and challenging me as a man and as a photographer.

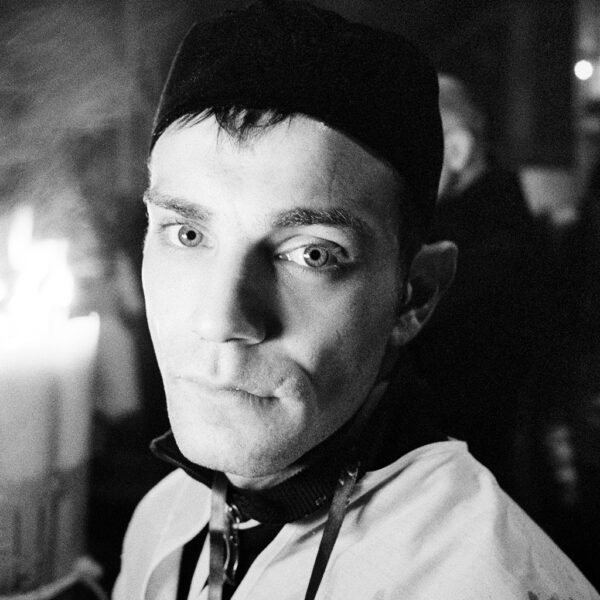

In 2010 I had the unprecedented chance to candidly approach the Cannelora of Butchers – á cannelora ri chianchieri. A fatal encounter, that pulled me in for many years. I cannot say exactly what was the source of this visceral connection. I knew that I wanted to belong to that group of men whose lives were largely devoted to the Festival and its ancient preparatory codes and performance. I wanted to be there, to experience it as one of them, from the inside.

Photography was my gateway. The entry key. The novelty that allowed me to carve out a space within an established and structured system.

In the Butchers’ Cannelora, I discovered a microcosm that met all of my needs.

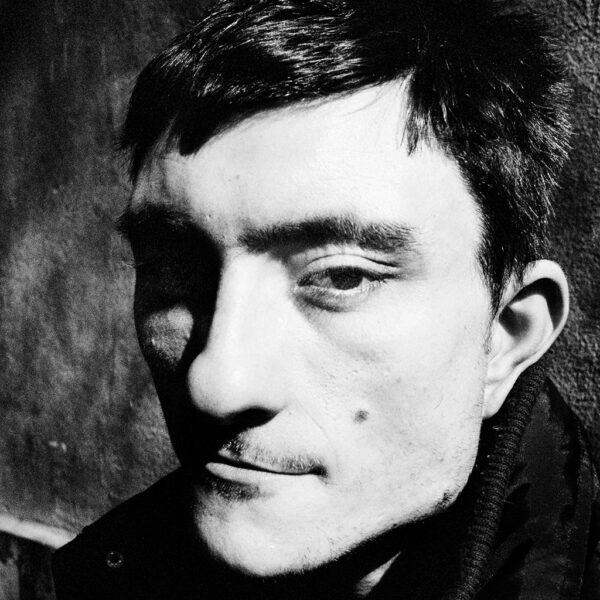

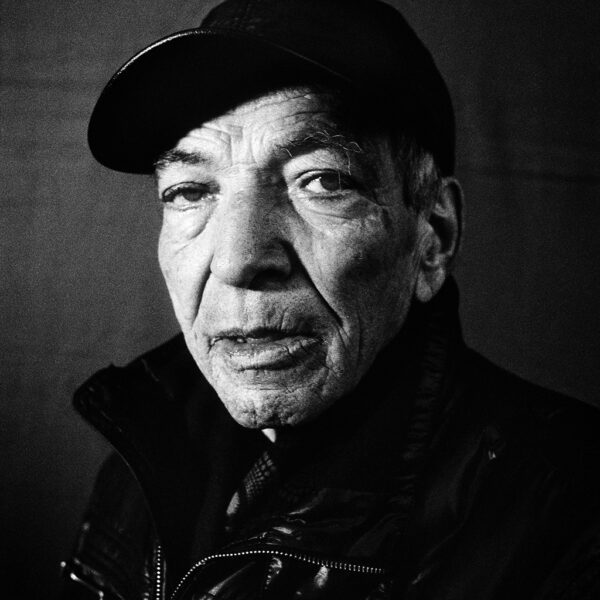

In 2011, I began printing and gifting photographs to the bearers and the other cannelori participants. No one had asked me to do this, but it seemed a natural way to enter their world. By the next year I was known as the photographer. Nobody knew my name, nobody ever asked me a personal question, but I was somewhat useful to the system. I had become part of the community. They had empowered me, I had their permission, their blessing even, to photograph things and people without any restrictions. Meanwhile, I had met the unofficial president of the cannelori, Saro Stramondo[1] – ú ziu Saro – who would become first my liaison and then a dear friend.

The Butchers’ Cannelora is an extension of Saro Stramondo. With the help of his son Luca and his grandchildren, Saro arranged and selected the bearers, directed their physical and mental efforts, dictated the music to the band. The cannelora was his raison d’être and remained so even while he was suffering from the illness that he would later succumb to.

He was instrumental in my photographic and human involvement, it was as if with him, with his way of doing things, his approach, his style and his work, my past found a way into the present.

I owe it in large part to him, to the relationship of mutual trust and respect that we were able to establish, the opportunity I had to photograph the Festival of St. Agatha and its articulate behind-the-scenes events all these years.

The legends I carried with me from childhood had vanished, reduced to nothing more than folktales. In their stead was the discovery of a fragment of humanity that has been able to maintain a very strong link with its past, its roots, with its popular origins, without which we lose our bearings and get lost in the present.

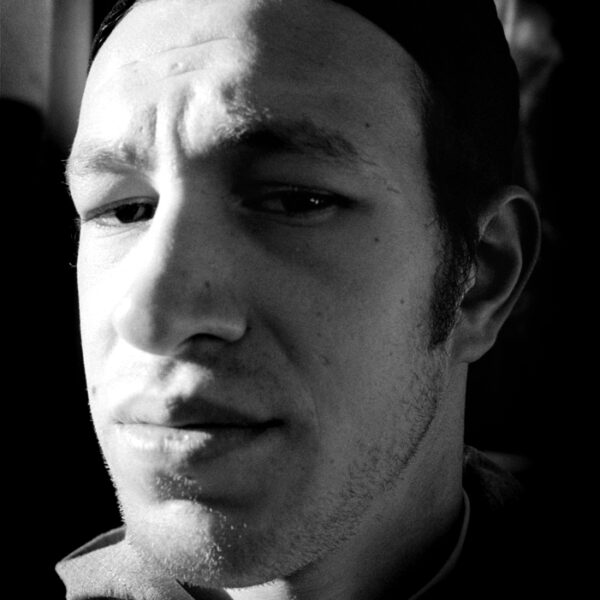

My intention was to tell the story of the human world that revolves around this cannelora. A mixture of toil, matter, bodies, excitement, limelight, redemption, happiness, an ULTRAWORLD of men who only have eyes for one woman who died nineteen centuries ago, their beloved Agatha.

Over these eleven years I have seen more than a few bearers switch, some have passed the baton to their sons, others have changed their roles, and some have left, then returned, and maybe left again. One thing, however, has never changed: the people – the carusi – who swarm around the cannelora like moths. I watched many of the boys grow up, fascinated, like I was, by the rites and ceremonies, the authority of the old men, the strictness of the hierarchies, their joy, the prominence that made them feel at the center of their city and its history, and I too grew with them.

In 2018, after a long battle with cancer, Saro Stramondo died at the age of 68.

With him died everything I have recounted so far, but most importantly, a way of life and experiencing the world expired. The ULTRAWORLD I was addicted to and overdosed on for many years was over.

The following year I returned to Catania to pay homage to him and to experience the Festival, but his passing marked a point of no return for me. I missed the soul of those days.

To me, the celebration came to an end on the morning of February 6, 2019.

[1] The surname Stramondo could be roughly translated to Ultraworld